"The Art of Pipes and Faucets" by Abbie Lahmers

Drew slipped out of the hospital last week and has been loafing around the neighborhood ever since. I spot him on my way to Pilates. If I’m late again, Diane will have me doing breathing exercises in the corner for an hour “to address your fear of hyperventilating.” This fear she singles me out for is actually acute and specifically involves a fear of acting on a stage or wandering into an improv group by accident where I am instructed to pretend I am someone I am not in a situation I am not in. It all seems absurd to me, acting. I don’t know where people find the words to do it, how they can become so spontaneously someone who isn’t real.Drew startles over the sight of a crosswalk sign, clutching onto bulky bandages obscuring his nose. He jumps when the sign says walk. Go on, Drew, it’s okay to walk. You have two working feet. I imagine I’m standing next to him on the crosswalk saying this, giving him a little push to make him go since the sign isn’t enough. I put my face close to his ear—but it isn’t intimate, this moment. A placeholder for intimacy.“Get your life back together, man,” I say, my mouth so close to the steering wheel, my breath fogs it up. I don't even notice when my light turns green until the SUV behind me honks.My sister dumped Drew a month ago, diminishing his poise in a tragic way—he seems to only wobble now, primitive arms dragging, his head swaying. He says he's perfectly fine despite losing, in some small way, his center of gravity. Sherry’s been making papier-mâché masks to help her through the breakup. It started with felt masks embroidered with glitter glue, which she made at the office to help a coworker who was throwing a party for her child. Now there is a collection of zoo animal faces lining Sherry’s once-empty mantel, a vat of papery soup in her kitchen. “The plaster makes my hands feel old and crusty like a widow’s hands,” she whines on the phone. I suggested origami, but her fingers aren’t nimble enough.As for me, I’m learning to be more graceful. Learning, also, to drive steadier, to make fewer sudden movements, which is why I go slow even with the SUV tailgating me. A lesser woman would hurry through life, would drive fast and far, when really there's all the time in the world. I go to Pilates to teach myself how to breathe slower, to teach my feet to keep pace with my breath. To earn my tips unfolding my arm at the elbow with a tray full of Diet Cokes on my hand and not spill a drop, weaving through the other waitresses with food on their arms and not ruining the choreography.“Drew, one of these days, I’ll take you to Pilates,” I say to the steering wheel.*Sherry and Drew rushed into their relationship, moved into a two-bedroom apartment with our brother as soon as they could. It was around the time our parents moved to Alaska to rekindle a flame in the midst of an uncaringly beautiful wilderness they discovered through reruns of Northern Exposure. They left me with the house.They deemed me the least likely to succeed, their genetic charity case. It’s wonderfully simple, a mint green box with most of the childhood artifacts still intact, inherited reminders that the place used to be lived in, its walls stretched and used like an old sweater. My sister’s little doll house full of clothespin men still leaning against furniture, my mom’s Precious Moments statues with their lifeless teardrop eyes, and my dad’s key chains from every airport he’s ever been to. I visit Sherry’s cramped little apartment sometimes, but the building is old, and she’s always trying to renovate in small, hardly-influential ways—a few sea-foam green walls and a pasta arm she installed herself. It’s come to a point where I associate her with the welcoming smell of paint primer.Before it was abandoned and bestowed upon me, the house was dry. The first symptoms settled in gradually—first a little overflow gurgling up in my sink, then a weak wave gushing onto the floor. I found what I assumed was the drain hose, but could only figure out how to look at it with scrutiny, pondering its sickness. I squeezed it gently. No fever.Finally, a week ago, the dishwasher poured out all of the water it ever had onto the tiles, saying, no, I’m not okay—believe me now? The tiles cracked and tessellated into the bottomless hole below, and the ocean chased after.I didn’t know this happened to people.Now it's clear that my dishwasher is a portal into an ocean and everything’s spilling over just now. I pulled out a pile of gunk from the drain and came up with a NECCO candy wrapper and some torn-up plastic lobster bibs. I think the water comes from a New England beach because it’s always a little chilly when you stand next to it. The sand is starting to pile up in shallow dunes by the pantry where Mittens thinks her new litter box is. It’s no place tropical or pristine. The water isn’t bottom-of-a-swimming-pool-blue.I was there when the pipes finally burst. The water churned in the bottom of the machine for a while, a shallow secluded hot spring cooking my dishes. Waves gushed out in the tiny space of early morning when I lay in bed with eyelids crouched half-open, ready but not ready to attack the day. Mittens and I felt helpless so we pawed at the water. She pricked her nose on dish shards and glasses. The old Fiestaware was a pointy mosaic at my socked feet, the plates I once ate off of as a child now fractured into bright shards. I could start a collection of coffee mug handles and call it found art.“Well, you know, that tiling had to go. I’ve been telling you all along,” Sherry said on the phone the next morning.“I know, but isn't this unnatural? I was supposed to invite a stranger into my home and have him tear the floor up for me. It shouldn’t do this on its own.” I twirled the cord in my fingers.It felt like we were teenagers again, only we were speaking across a distance instead of her yelling at me from the bedroom to quit hogging the landline.“What are you going to do about it?”“I don’t know, but Mittens is upset.”I wanted her to tell me what to do. She was quiet for a long time, like she had fallen asleep. I hung up after counting to sixty five times.*Drew comes over in the middle of my crisis to talk about Sherry. He stands in my threshold, peeling an orange and shaking his head at my dishwasher. “I’m waiting it out. Nothing’s certain ‘til it’s certain.” He takes a few idle steps, his shoes smacking the thin layer of water that coats my floor, but he doesn’t seem to notice. The orange is a struggle for him, his face still mostly a bruise.“You can’t argue with that wisdom,” I say, feeding him praise like I’d feed a goose—little pieces of bread, one at a time, then backing away before he gets too close.“So you’ll talk to her about us…you know, getting back together?” My kitchen is overwhelmed with the citrusy blend of real orange and artificial lemon dish soap. Orange strings stick to Drew's teeth. Does Sherry even know he’s here? I try to extract a plate wedged in the jumbled metal tracks so I don’t have to look at him when I pretend to not know what he’s talking about.“That reminds me—Sherry has that plumber friend. Maybe he’ll help.”The water stirs as he inches backwards. “Okay.”Maybe I should comfort him. “It’s okay.”“Yup,” he says.The problem with Sherry is that she always wants more—more lovers, more brothers, more eye shadow and lemonade. More projects and more movie marathons. Sometimes she doesn’t know which of these things she wants the most and substitutes one for the other, and it makes her upset without knowing why when she gets lemonade instead of eye shadow. Drew knows this already. He’s not the right thing for the moment.*There was a confusing time in my Sherry's life when our brother, Ben, ran off to marry a boy in San Francisco and insisted that no one understood. He was our brother who sipped salty dogs on family beach vacations and talked to all the strangers, saying he was there for business, not with us. He once left a wedding early with a redhead in a pink princess gown, blue eyelids and nude lipstick, to go see the Cornish hens she raised in a hutch. He woke in the bed of a hay wagon missing his cufflinks. Ben lived with Sherry only weeks before Drew moved in with her. She always wanted us all to hang out at bars on weeknights together, “Like crazy kids without jobs. We’ll look beautiful!” She said this to her reflection in the mirror while Ben and Drew sat in her kitchen, barely looking at each other, saying nothing, maybe wondering if they knew the same secrets about her.Drew might have thought, Does he know about the time she cut her foot on the shower faucet and we had to stop fucking because of all the blood?Ben might have wondered, Did she tell him about the Barbie nunchucks she used to make by tying their hair together and swinging them around above her head, screeching ‘kiai!’?When I went out with them, they'd each pull me aside and promise to be my secret wingman so long as I didn’t quit going out with them when I found a guy to shack up with. No one ever found me a guy to shack up with. I usually ended up wedged in our corner booth with Drew on the other side of the horseshoe. We would peel the breading off all the asparagus appetizers and suck them down like green straws. I filled him in about the parts of Sherry he didn’t know. About how I loved my Barbies like they were skinny sisters, but everything my real sister did was art to me. So I helped her with the knots. We were both wild about Sherry, in our own ways. After a few songs, Sherry would return and spin Drew all around the dance floor.We quit going out when Ben left. Drew tried to fill the void in her house, but I think Sherry always hated seeing his toothbrush where Ben’s used to be.*I don’t know anything about plumbing, but I don’t think this has anything to do with pipes. I think it’s the same thing as a house settling into its bones, but to a different degree. My house is sicker than most, and I keep telling it, “You haven’t even lived yet. If you just learned to be happy, things would be okay.” But it keeps pouring out oceans. Sometimes it’s almost as if it’s rejoicing, or getting back at me for saying I wanted a beach house.Drew moved in not because I consciously invited him, but because he spent so much time sitting on the couch watching Dr. Phil that it felt inhospitable to not offer it to him as a bed. It was when he bought a new light bulb for a lamp I’d long since written off as useless that I knew he had to stay. The living room was still dry, livable.I didn’t want him to see the transition taking place, his gradual, unintentional migration into the childhood home of his ex-girlfriend, because I was afraid it might startle him away. I had caught him sitting in her old room once. Even though most of her stuff was gone, he was crouched in the middle of the floor with a shoe in his hand and bloodshot eyes. “There was a spider…” he explained, “but it got away.”When he left one night to get pizza, I laid out a blanket and a pillow on the couch and slipped a spare key underneath his wallet. At first he said, “No, I couldn’t,” but after a few days he brought his toothbrush. Mittens, who loves legs indiscriminately, is pleased with the two new posts to rub against.I am in the kitchen with bits of ceramic mugs spread out all over the table. My jeans are rolled up to my shins, bare feet dipped in the water. Drew is on the couch, one arm tossed over his head, clutching the remote, his sweat-socked feet flopped over the coffee table. His talk shows are on. The host is berating a young woman about her weight. I pick up my coffee mug pieces and arrange them into a boat. It doesn’t look like anything so I scatter them around, knocking one onto the floor where it lands with a splash. I wish I knew more about mosaics. Most of the handles are all still intact so I think about hanging them up to make a sad monument to myself, a woman defeated by her own kitchen.I curl my hand into a fist, as if to do something violent, something drastic or loud or shattering like my dishwasher is so fond of doing—and yet the dishwasher does these things so gently. I can’t mock the art that comes out of my dishwasher, but I don’t know what art is. I dig my fingernails into my hand, pull them out to see what I’ve done. Normally I look at the moon right after it’s brand new and say it looks like a fingernail clipping. Now I look at my hand and say to Drew, “It looks like crescent moons.”Drew grunts, “Huh.”I hide the hand under my knees. “Do you want to go somewhere? Outside or something?”Drew turns away from the TV. “Why? What is this all about?”“I’m trying to cheer you up. Come on. We’ll go to Pilates.”*Before I had Pilates and before Sherry had Drew, I was seventeen and counting how many breaths I could take in a minute. And then heartbeats. And then for ten minutes. Just sometimes when I needed to be grounded. Or lifted up. It did both these things somehow. It became my religion. This was after I dabbled in Hinduism because I liked Bollywood fashion, the bangles and crimson fabrics, the gyrating hips and bare feet. I wanted to present myself, a ball of color, to all the classmates who wrote me off as drab and tasteless. Even though I was. I asked my mom where I could get bindis to put on my forehead, and she returned from a local church flea market with a bingo marker—“Just press lightly,” she said. I wanted to shroud my walls in tapestries, which made me realize how superficial it all was, my Hinduism. It was not authentic.The truth is, I peaked in high school. I was the best person I could have ever been when I was seventeen and counting my breaths like they were decades of my life—deliberately and with a twinge of loss at each one’s passing. I didn’t care about anything and it made me so invulnerable.It started with a splinter, a peregrine inhabitant lodging in my skin, brainwashing me, I think. It whispered, “There’s nothing wrong with having a piece of wood wedged into your palm. This will cure itself.” I practiced writing with my left hand and skipping over conjunctions and pronouns when I wrote in my diary to make it easier. “Sherry pierced neighbor Steve’s ear. Got blood on my pillow. That whore,” my seventeen-year-old self scrawled in chicken scratch.The wound did not cure itself. It grew a fire. A red sweaty one in the center of my hand. The piece of wood, my friend, became a speck in the center of infection. I hid the whole thing in my pockets, in my father’s roomy work gloves, rolled up in the bottom of my sweatshirt when I was out of resources, my belly button exposed to cover up the secret. We were too far into the relationship for me to admit that I had trusted the splinter in the beginning. It would be too embarrassing to reveal him now.Ben found him at last.“Jodie, you idiot. Your whole goddamned hand is going to rot off.”“Nooo! It’s just a scratch, leave it alone.” I crammed my hand back in its fabric cocoon. He pulled me by the neck of my sweatshirt and drove me to the ER.When we got back Sherry acted like it was her hand that had faced a ravenous splinter and come out intact. She loved casting Ben in a heroic glow, loved relying on him. “That whore,” I wrote with my healed right hand. “She just wishes all the bad things would happen to her.”I’m not saying I miss the splinter, but it was nice to have something that Sherry didn’t. That Sherry never would have because she was smart enough to let go of a silly skin wound.*From across the room I can see Drew's disfigured profile where the slightly protruding mass of his swollen nose is still shiny and red.“Pilates? I don’t think so.”He says this to Mittens. She sits across from him, flicking her tail back and forth, pretending to be a regal cat instead of a cat from a broken home. I don’t like telling Drew what to do anymore since Sherry isn’t around to stick up for him, so I do it from a safe distance.“Drew, do it for me. I need to get out of this house.”Mittens pauses, her tail waving for emphasis. Drew nods.“No, you’re right. This is my fault. I’ll just move out, and then you don’t have to worry about me being here all the time.”I trace tiny faces in the table with a mug handle, following the repetitive whorls of the fake wood. My fingers are raisins. It’s as if the water is resting inside. The couch springs sigh as Drew stands. I don’t want him to leave.“Relax, it’s just Pilates,” I say.But I know I have done it. I scared him away.If I don’t acknowledge him as a fixture in my house right now, he will have never been here at all. And maybe that’s what the flood needs. To be declared irrelevant. To be not a part of my life, and with Drew, it would slink away back into the shadows. It would be a story I would tell my coworkers that they would never believe.Drew and I face each other, finally together in an intimate space even though he is in the living room and I am still in the kitchen. I hold up the piece of ceramic. “Fine. You don’t have to come along, but clean these up, okay? I’ll pick up some frozen lasagna on my way home. Preheat the oven in an hour.”*“It never even leaves the kitchen, Sherry. Not a drop. I don’t have flood insurance, so why bother with it?” I talk softly so as to not wake Drew in the other room. I cradle the receiver in my shoulder as I squeeze through the head opening of the old lady flower nightie I bought at Goodwill today because I was afraid to come home and rediscover that the whole thing was still not a dream. From my perch on the bed I can see me in my mirror. I am a baby blue ruffle. The bunched-up fabric stops at my hips, refusing to fall the rest of the way.“Maybe I’ll nurture it. Let it erupt for a while and eventually it will become a hot spring,” I say, leaning my ear into the phone, into Sherry’s voice.“Eww, Jodie, c’mon, you’re being gross. Be an adult. You’re a homeowner. You have to start being responsible.”I stand and let the rest of the fabric fall to the floor around my feet. “I bought a nightgown. It smells like cats and egg salad, but my legs feel free.”“I don’t want to talk to you if you’re acting like this.”*The next day I work and come home exhausted. Too exhausted to turn on the light in the living room or to think about Drew because who is he, anyway? Just my sister’s deadbeat ex. The scraps off her plate. I feel weird about someone sleeping on my couch. No one ever comes to my house. Not since my parents moved to Alaska to spend their retirement dog sledding or shooting up heroin or doing whatever it was that my parents did with their freedom from us. Mom calls Sherry every week, reciting little newsletters about retirement into her voicemail or talking about lifeless things like interior design and crafting, but I unsubscribed from the ritual months ago, so I don’t know anymore. Sherry has offered to move in with me before. Not as a mooch but as a roommate because we already know we can live together and only hate each other for short breaths of time. I think of all this as I look at the apparition on my couch. It is at these times that he is there without being there. He’s still just a remote possibility.Sometimes now I sit and wonder where all the water goes. It’s like watching the real ocean except with infinity confined to a small space.*Sherry felt like a disco princess the night it happened, I imagine. I don’t know how the whole thing went exactly, but I can recycle little glimpses of their eggshell romance and my sister’s tired old rants that I’ve seen and boil it down into something like this. She was decked out from head to toe in something shimmering, maybe orange. I can picture the costume she may have worn—the one from high school with the straps that crossed in the back. She took Drew to Drag Queen Prom Night—a dinner and a show held at Hitchcock’s bar. It was the first time she had gone out since Ben had left, and I wasn’t invited. It was just her and Drew, treading thin ice without mutual friends to keep them from getting too close to each other. She waves to the men in the table next to them, pretending she knows them. I imagine it was after the fifth queen strutted down the runway in a gold-sequined number that Sherry and Drew forgot how to converse. They deteriorated from there until they were nothing left but an empty sparkly dress and a pair of sweaty khaki slacks tossed in with a pile of empty martinis, light beers, and lemon twists.On the way home, Sherry cries and rubs her makeup off. I’ve seen this routine, her eyes smudged into bruises. She says, “I just want it to feel normal, like when Ben was around.”Drew mumbles something caustic but stumbles over the words, something like, “You two were always meant to be together.”“You always hated him!” She might say these words like an actress, like she’s on a stage and people are watching, applauding.Drew props her up by the elbow, afraid to hold her in his arms when she gets like this, and she pushes him away.I got the call at work—Sherry was sobbing. “I killed him, I killed Drew!”*The thing about Sherry and Drew is that they loved falling romantically, dramatically, tragically into one another’s arms. So much so that they became empty of anything real because, bored of each other, they could only invent drama, to stay interested and interesting. Because they came together to find themselves, to find vibrant beautiful people that they swore were buried under there, these lonely trapped divers playing in someone else’s shipwreck and wishing it had been their own. They breathe slowly to ration the air, submerged so deep they could never be discovered and welcoming the drunken numbness as the nitrogen narcosis sets in. Sherry and Drew were always waiting for that violent lurch of a breaking stern to knock each other off their feet, and all they found were tepid hugs and dead-fish handshakes.Drew went to the hospital after Sherry drunkenly shoved him off the sidewalk, and his foot got caught in the sewage grate, and his nose got bent out of shape on the asphalt. A domestic casualty. They always thought they’d achieve greater than that.*I wonder how people get the salt out of brine. If I became an entrepreneur, harvesting salt out of my dishwasher, then I could quit my day job and cherish my disaster. Maybe if I set out pots and pans full of my ocean water all over the back yard, the sun would pull the water out for me, and I could take my sea salt to the farmer’s market and sell it next to all those common garden vegetables and fruit preserves, alongside my Fiestaware mosaics. People would know me as the salt lady, and I would finally have a niche. The only thing that’s holding me back are the men in wetsuits mucking around my kitchen, trying to find the source of all the water. The plumbers keep asking me if I did it myself. They’re like drainage police, accusing me of kitchen homicide. “Where did you get all the ocean water?” “That grime over there looks like…algae? Isn’t it illegal to remove ocean fauna from their natural habitats?” “No, you’re thinking of coral…wait, is there coral in here?” “I saw something green and spongy wedged in the back of the machine.”“That was my sponge,” I say, lurking behind the imaginary tapelines that keep me outside of the investigation. They ignore me.At the end of the day, the plumber tells me all the water is weakening the foundation of the house and seems to think this is reason for prompt evacuation. He has installed a pump that feeds the water into the sewer as the waves roll in, and he avoids using the phrase “high tide,” but we both know the pump won’t be able to withstand a high volume of water. “There isn’t much we can do, ma’am. The source of the flood is…unnatural.” He rotates his hands around an imaginary ball as if he is containing everything that is natural within his palms.I want to scream back, “You’re unnatural!” but he wouldn’t understand the irony of his assertion. Here was a man trained in the art of pipes and faucets trying to understand an entire ocean.It doesn’t matter, though.Drew left today, and even though his scarce belongings still clutter my coffee table, I know he won’t be back. He went in for his last checkup yesterday, and the nose is almost healed. The swelling has gone down so much that he doesn’t even look like the Drew I found skittering across the street a week ago. He looks like Sherry’s Drew again.Sherry sent me the plumbers as a present to soften the news that she was moving to San Francisco to stay with Ben. She left me a voice message: “Sweetie, don’t even worry about it. I’ll visit all the time, and hey, I talked to this great plumber who really knows his stuff. He’ll be over at 12:30 to look at your pipes. I’ll call when I land in San Fran!” She hasn’t called yet. Maybe she’s still up there, soaring at 30,000 feet and daydreaming about her new life.*The ocean sounds strained, mechanical, like a fork in the garbage disposal. But the garbage disposal has been broken since the ocean overtook it. I pull up a chair on the wet tile and sit with it. It doesn’t look like an ocean anymore. The pump makes it look like a regular flood, like my house is broken instead of liberated. The pump sighs with every wave it inhales. Mittens, the little fool, rubs her head against the machine affectionately after all the times she rummaged around the water and emerged with shrimp—some to eat and some to drop at my feet. It’s the first time I’ve heard her purr in weeks. My girl. She wouldn’t survive in the wild without machines to dispense her snacks.The plumber was right. The walls have gotten so soggy that they’re ready to sag like paper.It’s almost time.I’ve rarely been to the ocean, but my dishwasher has taught me so much about the ritual patterns of the sea. The pump groans as it encounters high tide, and the brand new pipes the plumbers installed begin to tremble. I dig up the emergency wrench I keep in the linen closet and return to my flood. I unscrew all the bolts and bang on the exposed pipes a couple times for good measure, but the ocean doesn’t need me to release it.I used to think swimming pools were unnatural because weren’t we creatures born without gills and fins for a reason, and wasn’t that reason to remain on dry land and keep our water contained in drinking glasses? But now there’s water all over me, water everywhere. This must be what it’s like to be born.

Abbie Lahmers is a fiction MFA candidate at Georgia College and State University and a managing editor of Arts & Letters. Her fiction has appeared or is upcoming in Flyway: Journal of Writing and Environment (winner of the 2016 Sweet Corn Contest), Beecher’s, Pif Magazine, SLAB, and Lime Hawk.

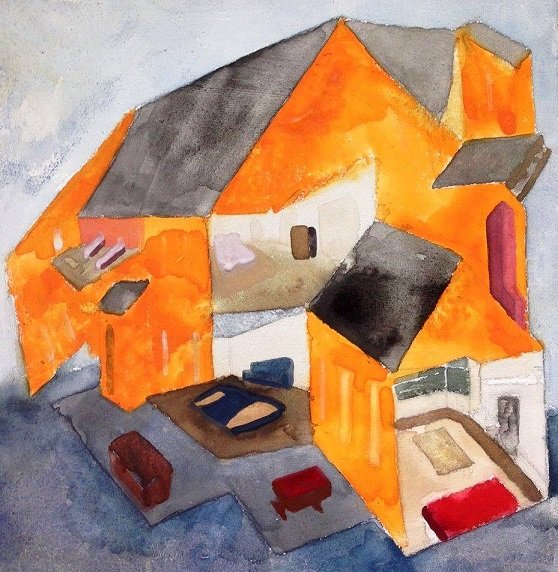

"Noon Hill Ave", watercolor and ink on canvas, 12" x 12", 2014 by Katharine Morrill.