On Submitting Poetry to Barnstorm

From the desks of our poetry editor, Johnathan Riley, and the poetry readers.

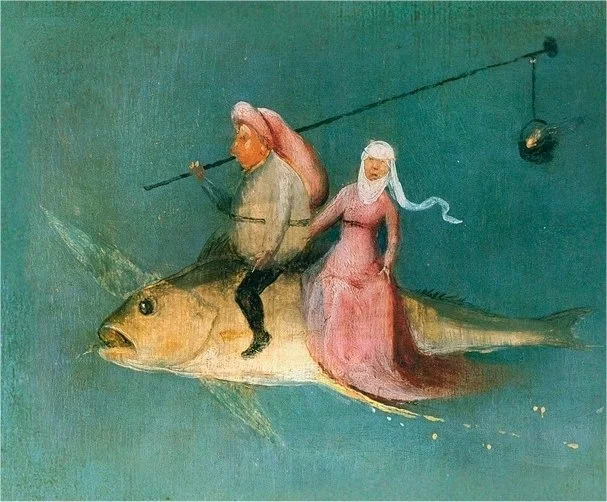

Detail from“Temptation of St. Anthony” - Hieronymus Bosch, c.1501

You’ve pondered, polished, written, rewritten, given up, gone back, given up again, and finally, you have arrived at place where your poem is ready to leave the comforts of your writing desk. For new writers and old finding a home for your latest darling often throws you into a sea of indefinite boundaries. We all know The New Yorker and The Paris Review, but they’re not the best places to start—they’re big fish with particular appetites and an abundance of food. Submittable itself is full of fish that are hungry, but with similar dietary preferences. Finding out which fish prefer your poetry is the whole racket and while we can’t tell you what every fish prefers, we can tell you what we, here at Barnstorm, like to eat. We’ve asked our dedicated team of Poetry Readers about their poetry pallets and what it is they look for in a poem when wading through submissions— this is what they said.

Emily Gore: MFA Poetry

“I look for poems that are insatiable. I look for honest poems, poems that take every word seriously and unseriously in equal measure. I look for poems that hold each word in the palm and inspect it from every angle, then the sentences, then the stanzas—poems that let words run around & play together on the floor—poems that make a mess. And I look for poems that gather the remains of the mess to reveal or revel in an idea or sensibility. A good poem presents an opportunity, a gift. It’s up to the poems to give, I can’t know what the gift is until it’s given.”

Seth Lewis: MA Literature

“As one of the few readers outside of the MFA program, my approach to reading through poetry submissions is more analytical than artistic — that is, I engage with the manuscripts not as a poet, but from the position of the critic. The quality of poetry, I believe, is decided not by a poem's faults; instead, good poetry is both aware of its intentions and certain of its merit. In this sense, then, the poems that I tend to select for publication are those which endeavor to actualize their raison d’être. Simply put, I assess each poem on the basis of its respective purpose, delineating that which evokes from that which merely displays.”

Cameron Netland: PhD Composition

“When I read a poem for Barnstorm, I cipher my decision in a threefold way. First, if there are no inert lines, cliches are nonexistent, and each word is a solid brick in the wall— then the poem has survived my initial mental gauntlet. Secondly, the poem must brave my craving for imagery. If the poem is wrapped in fog and smoke, buried under ice, or if it chose to wear striking clothes behind a blurred window, it fades from my care just like my vision. But if the smoke clears, the ice melts, or the window is opened then the poem must brave my last test, which is its gravity. The poem must be felt, and how much does one feel in half measures? If the poem is nonsense, it must be nonsense of great magnitude; if it is about love, then it must be like one’s first or last love, if it’s about death then make death as heavy as the sun’s pull on the earth. With all of language’s burlesque tricks, in the end, I look for purpose, imagery, and gravity. That is how I select a poem.”

Julia Roch: MFA Poetry

“In poetry submissions for Barnstorm, I look for a few elements, and it’s best when all three work together to create a cohesive creative work. The first aspect is attention to sound. For me, this is one of the main distinctions between poetry and fiction. You can tell when a writer has purposely chosen words not just for their meaning, but also for the way they work in the rhythm of the line and the poem as a whole.

The next aspect is form. Though it can be difficult to describe, experienced and talented poets can come to recognize when the content and the form of a poem are (or are not) working together in harmony. This is one of those “I know it when I see it” elements.

Lastly is the content itself. A good poem should resonate with readers and describe some story or emotion that needs to be told or felt. It doesn’t have to be serious or grave—funny poems are some of my favorites—but I shy away from poems that feel cliché or ones that depict gratuitously violent or gory subjects that are meant only to shock, and not connect with, the reader.”

Sam Rucks: MFA Poetry

“As a poetry reader for Barnstorm, I look for poems with movement. For me, the beauty of poetry occurs in the journey. Poetry is the process of moving to wisdom, to epiphany, no matter how big or small. A good poem can’t exist on wisdom alone. You can’t have a joke that’s all punchline and no setup. I also look for a natural voice. Words that feel spoken bring me in close and tell me to sit and stay awhile. Now, that’s not to say I don’t appreciate a beautifully constructed line; I just want to know who’s saying it.”

On behalf of Barnstorm, we wish you luck in your publication journey and, if after reading this, you are saying to yourself, “I think they’d like my poetry”, we would love the chance to read your work. Submit here.

Johnathan Riley is a second-year poet in the MFA program at UNH where he teaches an introductory poetry course. He is the current Poetry Editor of Barnstorm.